Separated by a crossroads and 125 years of history, it must be more than mere coincidence that the Black Sheep restaurant group’s 16th restaurant, New Punjab Club, has a direct sightline towards the renowned Fringe Club performance space, which itself is housed within the whimsical, white-and-coral striped Old Dairy Farm Depot and instantly draws comparisons with the similarly quirky aesthetic of Wes Anderson.

The American auteur’s cinematic style would ultimately serve as one of the main touchstones for the restaurant. As Black Sheep co-founder Syed Asim Hussain’s most personal project yet, New Punjab Club is intended as a theatrical stage as much as it is a love letter to his family’s homeland in the Punjab, a province that straddles the border between India and Pakistan. The result is a fantastical, gravitas-laden space that deftly combines colonial influences with the bombastic contemporary art of the region.

To unravel the restaurant’s tapestry of influences, we sat down with the fourth-generation Hongkonger to delve into his driving forces of family history, nostalgia, and the intoxicating craft of storytelling.

See more: T.Dining reviews New Punjab Club

How did you decide to base New Punjab Club on this particular time and place?

We as restaurateurs look at ourselves as historians of culture and cuisine – the restaurant is the result of our investigation into what happened in the shared province of Punjab between India and Pakistan post-independence. The essence of the restaurant is big, bold, boisterous, colourful, swanky, which is what was happening culturally within Punjab at that time. This is at an interesting cross-section of fantasy and nostalgia – of my nostalgia for growing up in Pakistan and my understanding of what this time was, and then the fantasy of what Pakistan would’ve been during the ‘50s and ‘60s.

What distinctly Punjab elements did you incorporate?

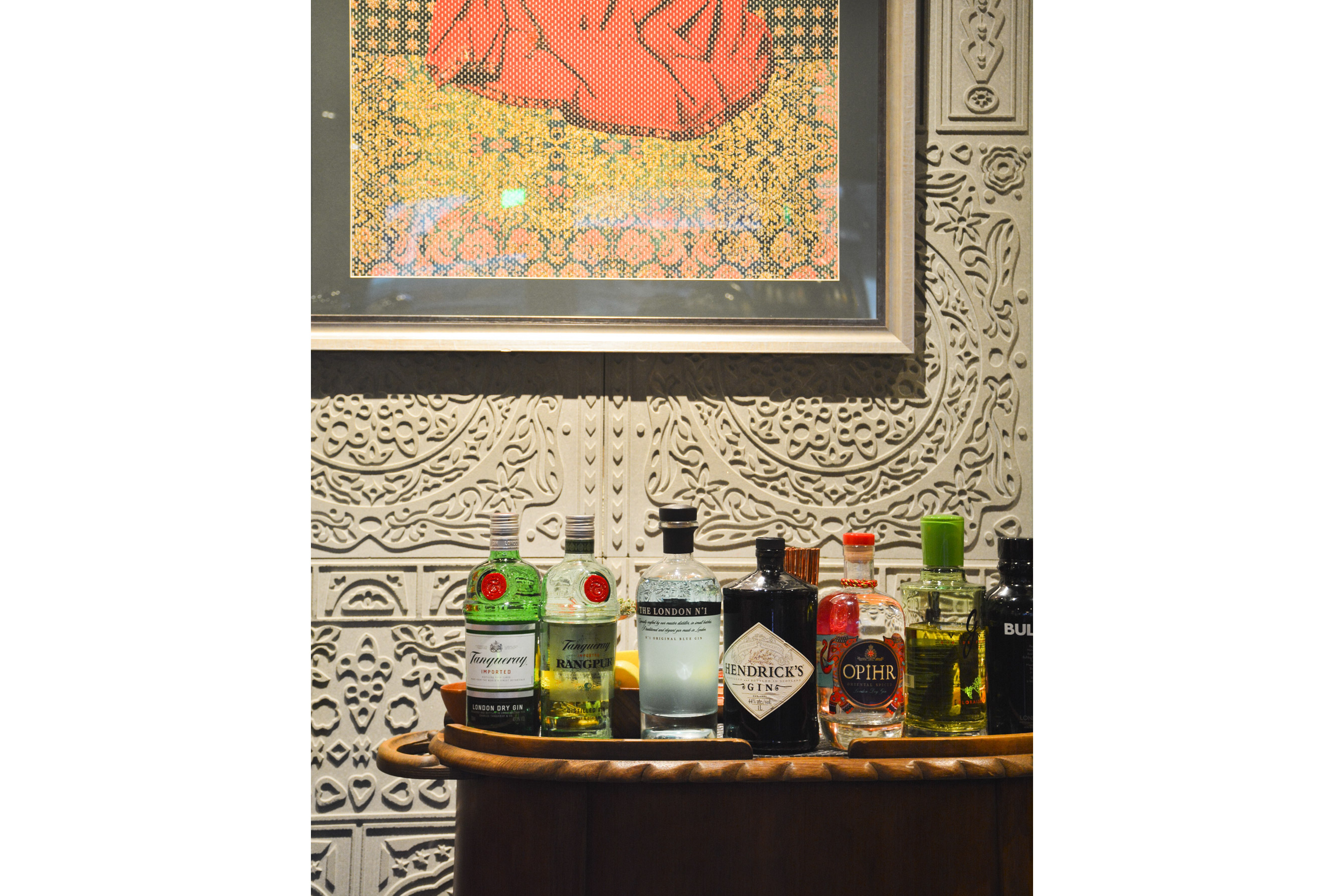

We say that Punjabis are not very sophisticated, but what they are is unapologetically authentic, which is an idea I kept coming back to. We want to leave all the Indian restaurant clichés at the door and rely on our memory bank and our understanding of what this culture and cuisine are, and that’s where the restaurant comes from. You’re sitting right now on a Victorian couch, we’re surrounded by beautiful contemporary Pakistani art, the plateware is an interesting mix of Churchill plates from the ‘60s, and with that we use local tabletops.

We’re trying to bring all these elements together in a very Wes Anderson [setting]. A lot of his work also sits at the cross-section of fantasy and nostalgia, and I think that’s where New Punjab Club comes from as well.

Were there any other films you were influenced by?

I love Wes Anderson as a storyteller, because this notion of what is fact and fiction gets so muddled. It’s almost unimportant to him, and that’s what we’re trying to do here too. That’s the only cinematic reference we looked at.

The Punjab Club in Lahore is the oldest social and athletic club in our part of the world. That’s where Kipling wrote The Jungle Book. So I did read a lot of literature around that time which gave us a lot of hints as to what this space was going to be. It was a place for thought leaders, for authors and poets and economists – a lot of intellectual activity happened in and around the Punjab Club.

You can feel the textures and say to yourself, someone thought about this, which is the hope that I have.

There’s a very diverse range of art styles here. Is it reflective of your own tastes?

Yes and no. All these pieces come from my personal collection and my tastes have changed over the years. I wanted to show a diverse look, because our guests might come and fall in love with one painting but hate another, so I wanted to give something for everyone. There’s a lot happening in terms of these elements coming together. Do you understand them all as a guest? Perhaps not, but you can feel the textures and say to yourself, someone thought about this, which is the hope that I have.

Punjabis traditionally allowed themselves to be very boisterous and have a zeal and zest for life. That’s what I’m trying to show in the bathroom which is very sparkly and shiny. During service, we play prose from a very famous Punjabi poet in the bathrooms. If you don’t understand Urdu, it means nothing to you, but at least you’ll think that it was thoughtful. In the true manner of Black Sheep, we try to think of as many elements as we can to put this thing together.

How did your childhood influence the restaurant design?

Growing up in Hong Kong, my parents had restaurants so it never seemed like work – it was just what we did. We would come back every summer and spend a lot of time in the restaurant, and those are my teenage memories. On a personal level, I also saw them struggle in the business so maybe my starting Black Sheep, especially opening New Punjab Club, is the coming of things full circle. My father had an Indian restaurant up the block for 15 years, and it was such a big part of my upbringing as a kid. In some ways, this is me picking up where they left off.

A lot of people come in and try to use this as another curry house, but we’re not that.

What about the Punjab is so evocative for the arts?

I think it’s the coming together of three religions: Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus. There’s also a Christian minority. What’s fascinating about the Punjab is it’s the only province in the two countries where the idea of being from that province is stronger than any nationalistic idea. What makes it more fascinating is this is a shared province between two wartorn countries, but we identify as being one on both sides of the border. Our waiters look at themselves as actors in a play. Our chef, sous-chef and manager are from Punjab – these guys have a strong connection to the story we’re trying to narrate. I sometimes have to pull themselves back and say, we’re going overboard, let’s come back a bit. For a new restaurant we’ve won a few awards because we’re trying to tell an authentic story, a story that we believe in.

The dramatic lighting helps as well.

It does. When you’re walking in, you feel like you’re about to see a play or a Punjabi film. My big mission statement was to not let this food be ethnic food anymore. We’re trying to find a new context for this story, and we have been able to do that thus far. A lot of people come in and try to use this as another curry house, but we’re not that. We’re not going to let these outdated ideas shackle us. We’re trying to bring these references but use them in a manner that hasn’t been shown before.

There’s a very strong sense of irony here. Is that reflective of your own sense of humour?

Yeah, my humour is a little bit self-deprecating. That’s where the fun logo and the pink [colour scheme] come from. I want to have a lot of pride in the work we’re doing, but also not take ourselves too seriously.

I do want to overdo it, for us to go overboard. That’s how you break away from the shackles of preconceived notions.

Why do Indian restaurants need to have [Persian] carpets and play sitar music? Even the uniforms here, I worked with a designer back home to design them. The founder of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, used to wear these beautiful suits, so we looked at old pictures and felt that it would represent the world that we’re trying to build here.

We constructed a story and the guys all understood the story. That’s one thing I’m very proud of. Even the ones who didn’t grow up in that story, we work very hard on our side to explain the story to them. Of course all these [design] elements are really beautiful and they construct a beautiful room, but these guys make it a beautiful restaurant.

Is there anything you would’ve done differently if New Punjab Club was located outside of Hong Kong?

This is a small canvas, a nine-table restaurant. I would’ve loved a bigger canvas to work with, but for the most part I’m very proud of the work we’ve done. We’ve executed this at a very high level, and we’ve almost created a new genre in Indian-Pakistani cuisine. Nothing like this exists. No-one has taken one province, one time period and said, what can I bring back from this? This is how great movies are constructed, when the subject matter is very narrow. Perhaps this isn’t the only story we’ll bring back from India and Pakistan. We have a long history, so there are other stories from different time periods to explore. We look at ourselves as storytellers first and restaurateurs second.

The post Why the New Punjab Club is designed like a Wes Anderson film set appeared first on Home Journal.